The only things that are certain in life are death and taxes. Oh and (with a brief respite during the pandemic for reasons that deserve consideration but which I’m not going to delve into here) the near-annual piece on the OfS website about grade inflation:

- 19 Dec. 2018: Universities must get to grip with spiralling grade inflation

- 20 Nov. 2020: Grade inflation figures show nearly half of first-class degrees ‘unexplained’

- 12 May 2022: Universities must not allow a ‘decade of grade inflation to be baked into the system’

- 20 July 2023: University grade inflation starts to drop, but half of top grades still unexplained

- 10 Sept. 2024: Proportion of top grades falls to pre-pandemic levels, but nearly half are still unexplained

- 15 Jan. 2026: Proportion of first class degrees falls for third consecutive year, but nearly 40 per cent of top grades cannot be explained by statistical modelling

Yes a change of tone over the years, most notably this year’s headline which reads like the previous one, only peer reviewed and edited by committee. But essentially the same story written each time OfS publishes a report on this issue. An activity now looks as though it has been delegated to an LLM (which at least would save some of OfS’s budget, otherwise known as student tuition fees).

the frame shifts

What has changed this year, of course, is OfS opening a new front on this issue with its report last November on degree classification algorithms. The interesting but inadequate modelling that has underpinned the press releases quoted above, looks positively robust compared to the regulator’s decision to put universities on notice that it does not regard classification algorithms involving multiple pass or credit discounting as robust and appropriate. (Far more interesting and illuminating than OfS’s report is the piece that Jim Dickinson wrote for WonkHE, getting at what’s actually going on in the sector in respect of approaches to classification algorithms and why we see the differences in approach that we do).

And this in turn has led to changes in the sector response to this annual story. Typically this has involved universities defending the validity of the classifications they have awarded, both in terms of the reasons why student performance in assessment has improved and the rigour of the processes that assure standards. And we have seen this in the last few months.

What we’ve also seen is a revival of a once popular cause, still talked about enthusiastically by its advocates but rarely surfacing in more general discussions about higher education. Instead of the recent social media nostalgia for 2016, higher education has been getting a bit misty eyed about 2007. And more specifically the Burgess report of that year.

Because that was the year that a UniversitiesUK group led by the then Vice-Chancellor of Leicester University Bob Burgess (later Sir Bob) published Beyond the Honours Degree Classification, calling for a move away from existing approaches to degree classification towards the use of a Grade Point Average (GPA); and issuing a Higher Education Achievement Record (HEAR) to all students, providing a richer and more detailed record of their learning.

Now I’m not suggesting that this is quite as ubiquitous as the 2016 trend seemed to be in January, but nevertheless the revived enthusiasm for returning to the Burgess recommendations has surfaced regularly over the last few months.

principles and practicalities

In part this has reflected a reassertion and development of the arguments made in 2007 about the shortcomings of degree classification as a reflection of the learning and achievements of students during their undergraduate programmes; sometimes with an added dash of technology focusing on the way that AI undermines the existing, classification-based approach.

In the noughties through to the mid-2010s, when barely a year seemed to pass by without some further supplementary report from the Burgess Group or one of its offshoots, I was fairly firmly in the sceptical camp on a shift to GPA and the HEAR. I was unconvinced that the scale of the problem was as large as claimed. Now, though, I’m more convinced on the issue of principle; that degree classification is an inadequate signal of the learning and achievement of a student, and that there are probably better alternatives.

However, the why I was in that camp link to different dimensions of my chosen theme of legacy.

I was always concerned about the costs: the direct financial costs of systems and process changes; the associated costs in staff time; the costs of changing assessment culture and practice; the opportunity cost of the things not done as we were implementing GPA and HEAR. In other words, the costs of change; of addressing the legacy of the existing way of doing this.

To move from current approaches to classification to GPA and HEAR would still bring these costs. Yes, it can be argued that benefits are now greater as the failings of degree classification are greater and ever more evident. But it would be a huge amount of change. And the context now is entirely different to the noughties and 2010s.

In recent years the sector has endured, and continues to experience, a hard rain of structural change. And when I write the sector, what the sector is, of course, is its people; it is they who experience the consequences of these sudden, fundamental changes. And to extend the metaphor, the field that is the higher education sector is already flooded with change; can it really also absorb yet more change through something as demanding and impactful as replacing degree classification with GPA and HEAR? The legacy of the impact on the sector’s people of the recent years of change can’t be ignored when considering this.

politics

The revival of interest in GPA and HEAR also reflects something else, with several commentators suggesting that moving in this direction would spike OfS’s guns on grade inflation. No degree classification, no more annual beatings for the sector. With one bound, we would be free.

However, I’m not convinced the sector can escape the legacy with which it lives on this issue.

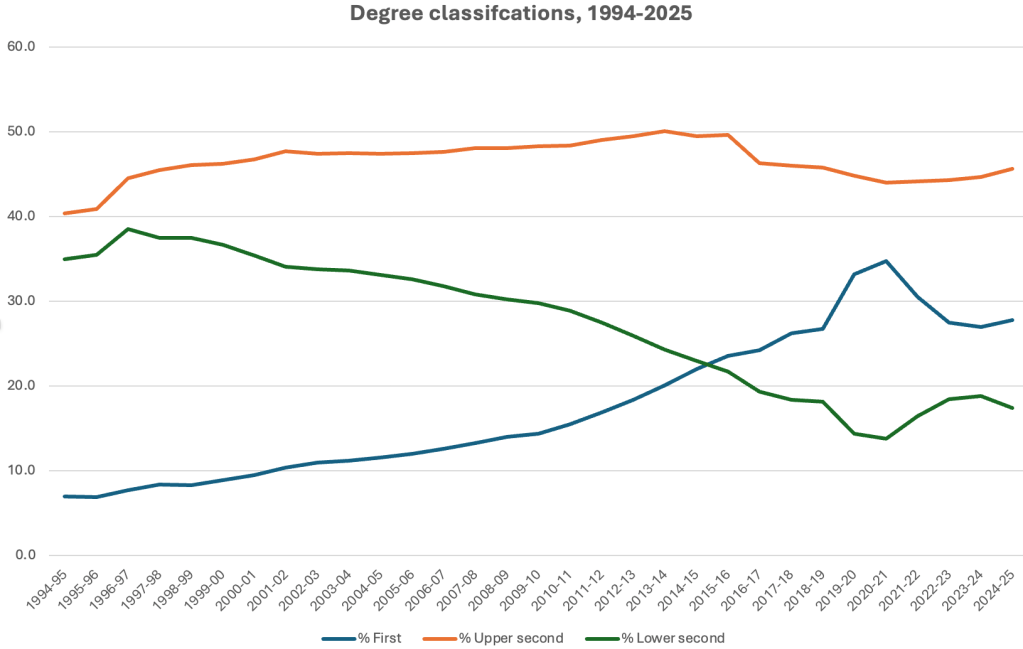

This legacy is the historic pattern of undergraduate degree classifications, and the way in which this has become entwined in the politics of the sector – and in wider politics full stop. The pattern of undergraduate degree classifications that forms the basis of this legacy is well-established, but for sake of completeness is clear from this chart:

Source: HESA

There is a narrative that when fees were hiked in 2012 universities responded to consumer demand and increased the number of ‘good degrees’ (if you accept that term) and firsts awarded. While I don’t agree with such claims, it does need to be acknowledged that the observable rise at this time only represented an acceleration of an existing, clear trend.

Like many in the sector, I believe that there are sound and justifiable reasons for much of this increase. However, this issue has metastasised in the UK body politic. It has become fused with the ‘more means worse’ critique of the sector, a critique that over the last decade has in turn been subsumed into the broader culture wars in what passes now for political debate (how we all look forward to the think piece, using the term ‘think’ loosely, each week in the right wing press by an Oxbridge graduate telling us fewer people need to go to university). And this means that if the sector were to move from honours classification to GPA/HEAR there is virtually no prospect of this issue disappearing from political debate.

Burgess was clear that were degree classification to be abandoned there would still need to be ‘an overall and definitive summative judgment’ [para. 60]; hence the GPA. If the sector were to implement this, we would just be making available more granular data for those with an axe to grind against the sector to slice and dice to confirm their pre-existing judgment that standards are not being maintained.

Of course it could be suggested (though I can’t recall any such suggestions) that the sector could go further; not produce a GPA but simply a HEAR or similar document so that there was no numeric data to be crunched by those seeking to bolster their views on the problems with academic standards in universities. This, though, would be a huge own goal: an abdication of our responsibilities as awarding bodies that would lay us open to the charge, from those convinced of the decline of academic standards, of fixing the system to remove the evidence of the alleged problem rather than addressing the claimed problem itself.

We can’t reform ourselves out of the need to explain the legacy we have as a sector, the trends over the last three decades in degree classifications. This work of explanation is hard if not Sisyphean, but it is unavoidable and essential.

choices – honest ones

Of course as a sector, or as individual institutions, we do not have to be prisoners of our history. We need not be captured by our legacies, but can choose to change; and on honours degree classification we are at the point where, from first principles, we probably should. However, we cannot ignore the legacy issues we will need to address, or the implications of these. Any move away from honours degree classification needs to adopt approaches that accept, understand the implications of and address these legacies.

Leave a comment