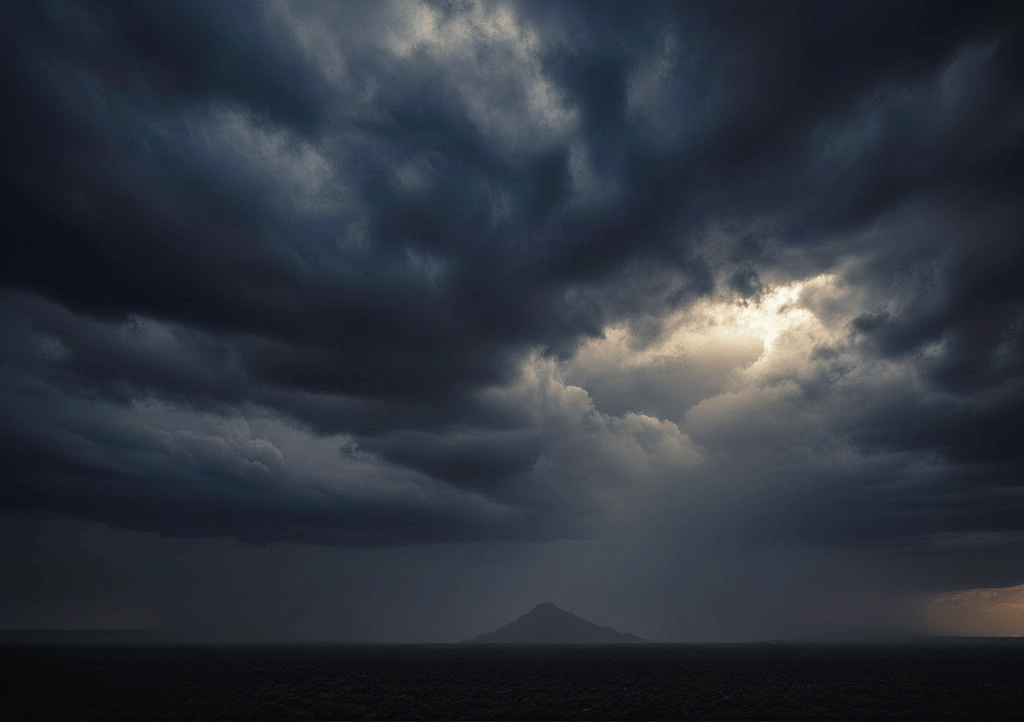

Collectively and individually UK universities are navigating their way through testing seas, but for those of us below decks there is at least one way in which the sector feels eerily quiet. The government review of English higher education announced last November.

hitting the ground reviewing

I’m sure that the DfE is eagerly (ok – maybe, diligently?) working away on this, and I’ve no doubt that this is drawing on perspectives, views and evidence from many current and recent senior and experienced colleagues in the higher education sector. For many of us, though, it feels odd and perhaps a little unnerving that something so potentially significant has such little public profile even within the sector.

All five of the areas covered by the review are important, but I have a particular interest on the strand looking at how to ‘raise the bar further on teaching standards, to maintain and improve our world-leading reputation and drive our poor practice’ – not least as when this commitment appeared in the Labour manifesto last summer, I was instantly interested in what had prompted this, what it actually meant and where it might lead.

It’s clear that work is taking place on this, with DfE engaging with sector bodies on the issue. But as yet, no public indication (at least that I’ve seen) of where this might be headed.

Helpfully WonkHE recently stepped into the gap at the start of the month with a list of suggested steps to deliver on this commitment. I’d agree with quite a bit of the list, and disagree with some elements. There was, though, one suggestion that would really concern me if it was taken up:

Require compulsory module evaluations with visible results for loan-funded modules … If students are paying for it (and increasingly borrowing for it), they deserve to know what they’re getting. Student reps can then work with the data and work with departments on problem-solving instead of being asked to supply feedback themselves.

let’s go round again

It’s not a new idea to suggest that this kind of data, currently generally only available internally, be published.

Back in 2011 the Coalition Government’s White Paper Students at the Heart of the System included an expectation for ‘all universities to publish summary reports of their student evaluation surveys on their websites by 2013/14’ [p.34]. The sector expressed concerns, and by the government response to the consultation on that White Paper what had been an ‘expectation’ had become ‘encourage[ment]’ [p.15].

Few if any universities felt spurred into action by this. There were good reasons for not doing so, and these remain valid.

fruit of the rotten tree?

Over the last decade the scale of the problems with Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) has become a well-worn topic over in educational research, with a large number of studies drawing out the very significant issues SETs raise in terms of the bias in results linked to the gender, age, ethnicity and other characteristics of the teaching staff being ‘assessed’ through SETs.

All of that is incredibly important, and by itself suggests why anything in the external regulatory environment that gave further weight to such a limited tool and set of data is a bad idea. There is, though, another even more fundamental problem with SETs.

some things are always with us

All universities look the same on the surface, but are all completely different once the surface is scratched. As someone who has worked across multiple universities, and been a external reviewer across many others, I’ve always found that to be a good rule of thumb.

Like all such rules, it doesn’t always hold up. And area where it doesn’t is SETs. At every university I’ve come across, there has been a varying but always significant degree of angst over low response rates to SETs particularly module level SETs.

The reality is that while there are some exceptions in the response rate achieved, getting a decent response rate is always challenging and is usually the exception rather than the rule. I remember being told by one company offering online SET software that a response rate of c.45% for module level SETs was good; and the flack I took when I mentioned this to academic colleagues in a committee meeting.

validity and value

And that flack was well-grounded, particularly given the tendency for response rates that often fall well below (and frequently well, well below) 50% to combine with the reality of the number of students on any given module.

Yes, we can all point to the modules with three, four or even five hundred students on them; but many, many of our modules have far fewer than 100 students. And such small population sizes for modules, combined with such low response rates, essentially means that the results we get from SETs come with huge, enormous error bars.

When I was responsible for the institutional SET policy and system, and saw far more SET results than I ever wanted, I was always struck by the size of these error bars. And by the inevitable consequence: how little (if anything) of value the results told the teaching team or individual teacher. Many, many times the result obtained was as likely to be a miss as hit the reality of the student academic experience or the quality of the module in question. Not infrequently, the SET results were (not to put to fine a point on it) garbage in terms of the quality of evidence they provided.

the weight the evidence can bear

I’m not suggesting that survey tools as a whole have no role to play in assuring and enhancing the quality of the educational experience. There are even ways of mitigating, at least in part, some of the issues that exist with module-level SETs as a specific form of survey tool.

The prospects of SETs hitting the target and accurately reflecting the educational experience of students increase with approaches that increase sample size and statistical reliability; and which focus on delivery by larger teaching teams at programme level, rather than the smaller team or single staff member who typically deliver an individual module. Stage and programme SETs can help achieve this.

And consideration of SET results at module/stage/programme level alongside the full range of quantitative and qualitative data, jointly by teaching teams and students allows nuanced and informed judgments to be made about the validity of the SET data – whether it is a hit or a miss in terms of evaluating the educational experience.

But to treat the results of module-level SETs as sufficiently reliable to be published information to inform student choice, is like seeking to build houses on land that is only secure and stable enough to support tents.

Leave a comment